« Ümparamu u munegascu ! » : Discovering the Monégasque language

The lockdown has just passed the month-long mark. For some, this is a moment to reflect on what we have achieved since our life’s rhythm significantly slowed down. Now settled into the new routine, it can also be a time for new challenges. And learning a new language can be one of the most rewarding challenges offered, especially when it is a crucial part of our culture. So… “ümparamu u munegascu!” (Let’s learn Monégasque together!)

The Academy of Dialects in Monaco has formally promoted the Monégasque language and culture since 1982. Twice a week, the Academy holds classes for experienced speakers and beginners, which are not currently taking place due to the lockdown. However, there remain a few weeks for you to immerse yourself in the Principality’s history and literature, and make good on your new resolution – to learn Monégasque.

Only 9,300 Monégasques

Claude Passet, Secretary-General of the Academy of Dialects, wrote the extensive manual on the dialect Bibliography of the Monégasque language (1927-2018). In the introduction, he underlines “the problem of the lasting-power of the Monégasque language in a principality of nearly 39,000 residents, of which only 9,300 are Monégasque, amongst 130 other nationalities.

According to the writer, “Monaco, despite, and perhaps due to, the hardships of an eventful 800-year long history has managed to preserve a sacred cultural identity on the isolated Rock, crystallised around the Genoese-originating language, which has now become Monégasque.”

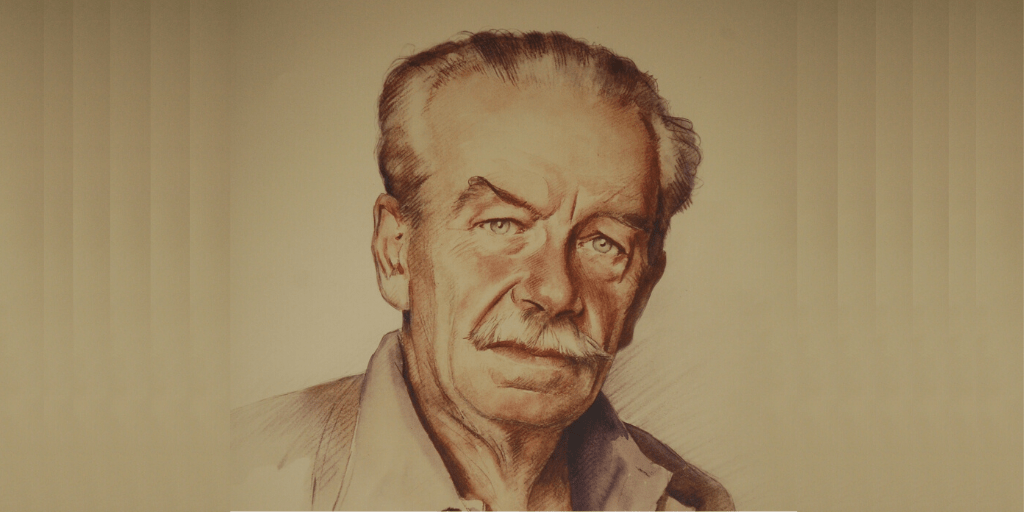

Louis Notari

Although residents have spoken it for many centuries, the first example of Monégasque literature appeared in 1927 with the publication of A Leganda de Santa Devota by Louis Notari. Henceforth, the poet became the father of Monégasque literature and a long battle for the survival of the language began.

Louis Notari

Louis Frolla

To better support it, academics and speakers first had to codify the language. In 1960, Louis Frolla published Grammaire monégasque. Written as “an attempt to codify our national idiom whose fall into oblivion we would like to stop”, the Prince’s Government instructed the scholar to print the manual. Three years later Frolla finished the first French-Monégasque dictionary, which would be published some 20 years later by Louis Barral and Suzanne Simone.

Compulsory teaching

In addition to these works, Prince Rainier III’s fierce determination to make teaching the language compulsory in all state primary schools from 1976 and private establishments from 1988 contributed to its survival.

In verse rather than prose

Passet directly quotes Les Fables by Louis Principale, inspired by famous French fabulist Jean de La Fontaine, as one of the essential works in the Monégasque. Given that no novels currently exist in the language, the Principality’s poetry is even more special to its heritage. Louis Notari once said, “Why did I try to write my Monégasque in verse rather than prose? Quite simply, because the patois of our ancestors seem so harmonious and gentle, that I would have thought I would have diminished its value by doing otherwise.”

Despite these efforts and its rich poetic form, the spoken Monégasque language is still likely to die out. Yet its literature is still out there to enjoy. Books by the likes of Louis Notari, Louis Canis and Robert Boisson mean it will never be forgotten or written from the history books.

Some useful Monégasque words

- Bon giurnu / Bungiurnu – Hello

- A se revede / Ciau – Bye

- Üncantau – Nice to meet you

- Per pieijè – Please

- Unde é a büveta? – Where’s the bar?

“Daghe Munegu”?

With every AS Monaco match, the two words flood the social networks. The message “Daghe Munegu” may seem mysterious, but it is the best way to encourage Robert Moreno’s players. Even if the pronunciation sounds a bit exotic, the meaning is very simple: “Go Monaco”.

Claire Guillou